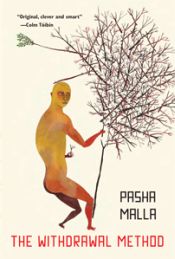

Stephany Aulenback and Pasha Malla are two extremely talented writers I met years ago, when the literary Internet seemed smaller, after finding and enjoying their work online. Now Pasha’s The Withdrawal Method, a story collection highly acclaimed in Canada, is out in the States.

Stephany Aulenback and Pasha Malla are two extremely talented writers I met years ago, when the literary Internet seemed smaller, after finding and enjoying their work online. Now Pasha’s The Withdrawal Method, a story collection highly acclaimed in Canada, is out in the States.

Below Steph (who posts an occasional Babies in Literature series at her site) admires Pasha’s depictions of children and childhood in fiction and asks him some questions. Pasha, being Pasha, asks some back. The conversation ends up being one of the best I’ve read on the subject.

At the end is a bonus video of the author reading from a poetry anthology he wrote in the 8th grade.

Pasha Malla does not write about generic children. His child characters are very vivid, very fleshy and real, if you will, and very different from one another. In some ways they are more vivid and individual than his adult characters, even when they make only fleeting appearances. In “The Past Composed,” a story mostly about the adult narrator, there is a very memorable secondary child character who is described as looking like “a mini-Richard Nixon.” There’s another very memorable secondary child character, Trish, in “Long Short, Short Long”:

Miss wasn’t really marking. Sort of, but more she was waiting to look up sharply and order some loud kid: “Out!” She hoped it was Trish. Trish in those stirrup pants like an acrobat, prissy, too eager with her head of perfect blonde curls and private voice training and hand shooting up fluttering to correct Miss on something Trish had learned at the Conserva-tree (like the Queen, she said it). “Miss, Miss!” and then, “Actually…” Doing harmonies when the class sung “Happy Birthday” even.

And when his children are the main characters, well, they are, in my opinion, his most memorable characters.

He places them in extremely truthful situations — it’s as if he remembers how dark, disturbing, and confusing being a child is. “Big City Girls,” for instance, features seven-year-old Alex, his older sister Ginny, and several of her fifth grader girl friends acting out rape scenarios (using Alex as the rapist) on a snow day from school. There’s a lot of that in these stories, actually — children acting out on each other adult behaviours, sex and violence for instance, that they don’t quite understand:

After a minute or so came the whisper of socks along the hall’s parquet. Alex waited, waited, and just as the footsteps neared the closet he swung the door open and pounced and grabbed the girl standing there and hauled her back into the closet, slamming the door behind him.

Alex was on top of the girl. He held his hook [ed: a toy plastic pirate hook] to her throat.

Can you be Jordan Knight when you rape me? said Heather’s voice in the dark.

Okay, what do I say?

Just be slow and nice, she said.

Okay, said Alex. Okay.

This kind of thing is common behavior for kids, of course, but it’s usually done in a very secretive way, and it’s the kind of thing that adults prefer not to see and not to remember. In the story “Pushing Oceans In and Pulling Oceans Out,” this taking on of an adult role happens in a different way — a fifth grade girl whose mother has died of breast cancer tries to act as a mother figure for her “slow” little brother. The strain of it all seems to be causing her to develop obsessive compulsive tendencies. This story is written in the first person, from the little girl’s perspective, and her voice is beautifully captured, something that is very difficult to do. In “Big City Girls” and “Long Short, Short Long,” Pasha uses a childlike close third person, and this works very well, too.

Yet while Pasha is relentlessly unsentimental in his treatment of childhood, he’s also hugely, hugely empathetic. When a child character behaves badly — as does Bogdan, a fourth grade immigrant from Bosnia who is both bullied and bullies — there is no blaming distance from the author, the way there often is when an adult character behaves badly. Instead, the character and the story are so carefully built that the reader, while certainly disturbed, also feels compassion and understanding — I should note, here, that Pasha taught elementary school for at least a year or two.

Some people seem to maintain a connection to childhood, and others simply don’t. There are some writers whose work, whether or not they are actually writing about children, seems somehow childlike in the best possible way — I think it has something to do with the freshness of their vision and also with a refusal to try to be sophisticated, with language, with plot, with ideas, simply for the sake of sophistication. And yet their work often turns out to be more imaginative, more nuanced, more risky and therefore, in these ways, more truly sophisticated, more truly new, than the work of writers whose work you would never describe as childlike.

I don’t think retaining a connection to childhood and having a “childlike” quality are necessarily linked. In Lawrence Weschler’s Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees, Robert Irwin comes across as curious, relentlessly inquisitive, easily delighted by simple things (like a good Diet Coke) — all characteristics I think we’d associate with some ideal of a “childlike sense of wonder.” But, despite being able to recall entire days from high school, Irwin claims to have no memories of his childhood. None. And it’s not because he’s repressing anything either; apparently he was a pretty happy kid.

Maybe part of it is that associating any particular characteristic with children is false; it seems to assume that kids are a homogeneous species. If someone has a “childlike quality,” it’s generally meant to insinuate a sort of wide-eyed innocence in the way, say, William Blake wrote about kids — 250 years ago. It’s one of the big mistakes we make in thinking about childhood: we’ve idealized one aspect of it, which is limiting. Being a kid is much more emotionally complex than that.

Well, I agree and I disagree. I think you can assign a few, a very few, qualities to children in general. But great fiction doesn’t come out of generalizations, does it? So yeah, I do agree that every child is as different from every other child as every adult is different from every other adult. And it’s clear from the variety of kids in your work that you recognize this. I started to count up all the children in the thirteen stories that make up your book — there are a lot of them, and they are very different from each other. Why are you so committed to writing accurately, truthfully, about children in your work?

Well, there’s just so much going on when you’re young, and kids feel everything so deeply — mainly because, I think, their understanding of time is so different from ours. If there’s one major difference between adults and kids it’s that as we age it becomes increasingly difficult to live in the present: we’re either working our way through the past or thinking about the future, how our decisions and actions now will either reflect upon things that have already happened or things that are still to come. (In Annie Dillard’s Teaching a Stone to Talk there’s an amazing essay, “Aces and Eights” about exactly this.) With kids — and this is one generalization I feel pretty comfortable in making — there’s only now. Think about how, when you’re young, you can fall in and out of hopeless, desperate, gut-wrenching love in the span of a week.

There’s this fantastic, perfect story of Graham Greene’s, “The Innocents,” which is maybe the best thing about first love I’ve ever read. Check this out; the kids he’s writing about are 8 years-old: “I remembered the small girl as well as one remembers anyone without a photograph to refer to… I remembered all the games of blind-man’s bluff at birthday parties when I vainly hoped to catch her, so that I might have the excuse to touch and hold her, but I never caught her; she always kept out of my way… I loved her with an intensity I have never felt since, I believe, for anyone.”

And that to me is why I want to write about kids: if “childlike” means anything to me, it’s a heightened state of experience, whether that manifests in joy or fear or happiness or shame or whatever. This is why childhood makes such amazingly fertile ground for fiction. And I think I’m still close enough to it and have decent and vivid enough memories of being a kid that I can do a decent job of writing about it — or I try to, anyway!

That really resonates, that you tend to feel things more deeply and more fully when you’re only there, in the present, and not projecting yourself into the past or the future by worrying about it. Except maybe the emotion of fear, actually, which is often requires a projection of the self in time. And kids do seem to feel a lot of fear. I know I did. And I’ve noticed it in my own little boy, Luke. What is fear but a kind of anticipation? So while I generally agree with the notion, I think it might be too simple to say that for kids there’s only now.

But here’s another thing about being a kid that’s rather at odds with his or her experience of the passage of time as slow — kids change more, and more rapidly, than adults do. I mean, you can feel pretty certain that a two-year-old experiences only the now — but eight years later, when the two-year-old is ten, that’s no longer as true. There’s such a distance travelled in those eight years in pretty much every way. Whereas I feel as if I’m pretty much the same person, with the same perceptions, I was eight years ago. So there’s this weird juxtaposition of slow time with rapid change.

Right, and in that tension is a world of possibilities for any writer who’s willing to think about it. What I’m wondering, though, is how writing for kids differs from writing about kids?

Wow, that’s a difficult question and I think you’re in a much better position to answer it than I am. Aren’t you working on a novel for adults right now and also on something for children? What do you think?

The YA book is on hold for now — and, with that said, Brian Doyle, a great writer of books for young people, told me this: never say you’re writing a YA book; let readers decide who the audience is. It’s good advice.

I think in fiction for adults about childhood there’s always this shared nostalgia that the author is trying to tap into; the stories are told from an adult perspective, with an adult’s knowledge and experience. That results in dramatic irony, which, even if not made explicit in the text, can create realizations that are shared between writer and reader about childhood or how the kids in the book are experiencing the world — I guess a subtle sort of winking over the heads of the kids. That sounds exploitive, but I think the best books about childhood are the ones where this is least obvious, where the reader is swept up into the children’s world and forced to keep up. Patrick McCabe’s The Butcher Boy is one (albeit horrifying) example of this.

I don’t really know what writing for kids is like, since I’ve done so little, but I’ve been thinking lately how unimportant the details and logic of narrative were to me when I was young. When I rewatched Star Wars as an adult, for example, I was completely astounded to discover that the movie had a plot — even though I could remember exactly what happened in every scene, and even entire passages of dialogue. And think about popular kids’ books like Goodnight Moon and even Where the Wild Things Are — so often the story, if there is one, is peripheral to mood, tone, imagery, and feeling. Those seem to be the things that attract and stay with kids about a book, far above what actually happens.

Has having a kid changed your experience as a reader and writer?

For the first seven months or so, Luke didn’t sleep. He cried around the clock and fed constantly. So initially, in my case, having a kid meant I didn’t have one spare minute to read or write. After that horrible time passed, I started reading again — like a starving woman. Writing didn’t start to happen again until Luke turned three, really, and then, soon after, I got pregnant again.

I must say that I am much more drawn to depictions of both motherhood and childhood in literature now and that I am much more sensitive to the tragic/traumatic, particularly if the trauma or tragedy has something to do with childhood. I’m absolutely blown away if it’s done well and I’m much more disgusted if it’s done poorly — for example, if I think it’s done to be sensationalistic. I guess I’m more emotional as a reader.

What are some books you’ve read that depict childhood honestly and truthfully?

Last year I started trying to compile a list of books that remind the adult reader what it’s like to be a child, classics not of childhood but about childhood. Rebecca West’s The Fountain Overflows was the book that started me thinking about that. And I’ve always loved A High Wind in Jamaica, a book that is certainly not for children but beautifully evokes childhood for the adult reader. How about you?

I love “The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner,” but that’s a story, and more about teenagers. I think Robert Cormier is one YA (sorry, Brian Doyle!) author with an unbelievably astute sense of what being young is all about. I reread The Chocolate War, a book I loved when I was younger, recently; it totally held up. The Butcher Boy, as I said, is another amazing portrayal of a certain type of youth, and so is Mario Vargas Llosa’s The Time of the Hero, although it’s completely different. The first section of Portrait of the Artist is pretty amazing in how it uses language to capture childhood experience — and then there’s Joyce’s story “Araby,” which does the same thing without so much linguistic experimentation.

Lastly, back to thinking about people as children: I find child stars the most difficult people to think of as kids — or at least normal kids who might have been students at the school where I used to teach. There’s this weird performance of childhood that goes with that territory, I think, and it feels so false– they’re like these odd little reversed Victorian versions of kids, like adults playing kids.

Which makes me think, somewhat digressively, about aging in the public eye. Those 7-Up films are interesting for that, and I know a few of the participants have dropped out because as adults they’ve found the experience too invasive. It must be impossible to be yourself when your childhood is so easily accessible: millions of people want to see Drew Barrymore at 9 years old, they rent ET. I wonder if instead of feeling robbed of your childhood, as people seem to say of child stars, this fabricated version of your childhood feels inescapable. It’s not so much that they didn’t have a childhood, but that they had one created for them.

I agree about the child stars — you’ve put your finger on it exactly. They’re just like adults playing children. I love those 7-Up films with a passion but I don’t think I would’ve wanted to be in one or have one of my children as the subject of one. The directors have done a terrific job of imposing a narrative structure on the lives of each of the children — but that’s the kicker. I think a proper narrative structure can only ever be imposed on a real life — real lives are too complicated, inexplicable, messy to be pressed tidily into a story — and I feel it’s up to the individual to decide on his or her own narrative structure. There’s something that feels a little dangerous, a little wounding, when it comes from outside.

I feel like I’m heading into the direction of pseudo-psychology here, and I don’t really know much about psychology. But your dad’s a psychiatrist, isn’t he? Does he talk about his work with you and do you discuss yours with him? Has he, or his field, influenced your fiction? How about your mother?

My folks are great readers (and writers — they’ve both been threatening to write books for years), but I think if I inherited anything from what they do professionally it’s a sense of inquiry and a deep, abiding interest in people. Both my mom and dad are also very excited about discovering new things, and — to return the conversation to childhood a bit — that was something instilled in me from the time I was very young. So I guess all that’s mirrored in my fiction, or I hope so, anyway.